5 Simple Emotional Lessons Learned From Video Games

learning to love yourself is hard

Fanbyte went the way of plenty other gaming news sites, devolving into a collection of guides and walkthroughs— Kotaku was hollowed out in a similar way this year, and smarter people than me have spoken about the demise of gaming journalism. What I miss are the oddities in Fanbyte’s feature section: I think my favorite kind of internet writing is done by people that don’t do a lot of it, there’s something fresh and easy and extemporaneous about it because there’s no real reason for it to exist. I miss when people wrote to find something out, rather than to explain something. Virginia Paine is a comics illustrator, but I think maybe one of my favorite games journalists owing to this sensibility that I’m describing— they may have only written six pieces in total, but there was such a patience and empathy to everything they wrote. You can’t find it now, but they once wrote something about the emotional lessons they learned from playing video games, because learning to love yourself is hard.

I thought I might share some lessons I learned this year while working through a backlog of games.

Jusant — not everything is your fault.

I had a lot of trouble progressing past the second chapter, which I found shameful because Jusant, even allowing for detours and wonderment, should only take you about six hours. But there’s this passage! A very annoying passage where your character wraps around a suspended fishing boat and scales the inside of what I can only describe as a giant cistern. The last bit to the top has no footholds; you’ve gotta jump. Time and again I would launch my player up, only to miss the rope draped just over the ledge above by inches. And so came the frustration loop: I’d put the game down, I’d do something else, I’d come back, I’d try hurling my player up the wall again. There had to have been something I wasn’t doing right, even with the scant things available to do— those are, swing, jump, climb, hold and release grip. I was just doing the same thing over and over without even assimilating any new information, which is well, you know, insane.

It wasn’t until weeks later when I was avoiding responsibilities on YouTube that I learned plenty of people were having this same problem. There’s a double jump mechanic the game doesn’t explain until an hour later, and there’s a whole habit of withholding in Jusant that commenters say make the immersive climbing sim a little too immersive. I felt a combination of relief and vindication. Put a dialog box in there, for chrissakes! You shouldn’t have to figure these things out on your own! Because isn’t climbing the barren face of the continental shelf hard enough without also being hard on yourself?

Jedi: Fallen Order — you can have your own feelings on the matter, whatever it is.

Initially I disliked this game for superficial reasons— because what the hell is a “lightsaber-resistant” enemy— but now I dislike it for legitimate ones.

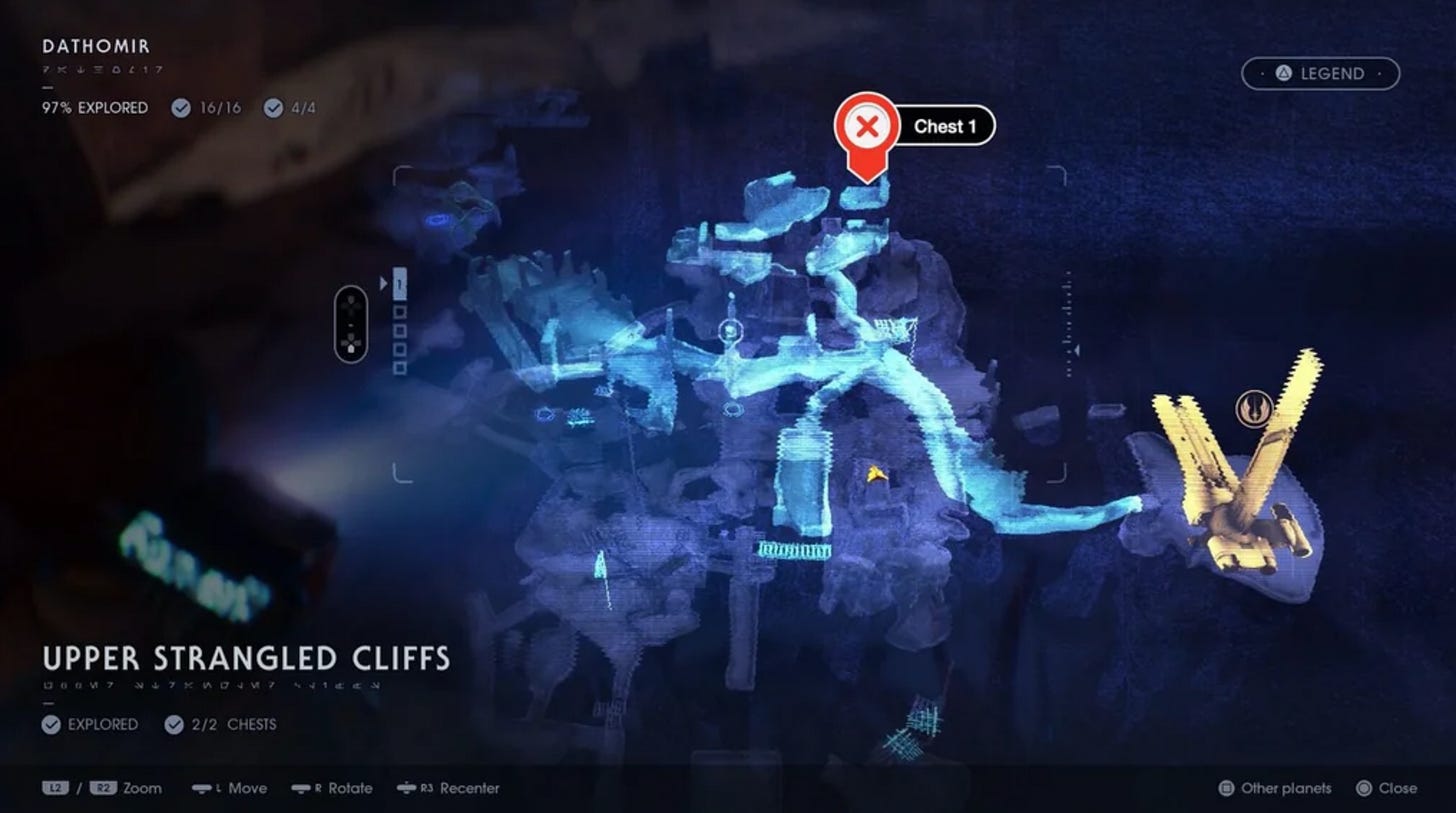

Just quickly, if Jedi: Fallen Order wanted to tell the god’s honest truth about itself, it would be titled Jedi: Return to the Mantis, since finding your way back to the ship, after completing the level, is what you are doing for most of the game. Cal Kestis’s physical and mental shortcomings as a space wizard are elsewhere easily explained by his severed connection to the force, which itself is a direct result of the traumatic events of Order 66—this is a tidy explanation, if it is annoying. What no one can spell out for me is Respawn’s fidelity to Lucas Arts’ prequel-era holocommunicators. They inform the design of Fallen Order’s map, and the map is famously illegible.

And if the idea behind thwarting any sense of direction is to prime the player to explore the world fully, then there really should be more waiting for you after a tricky passage of platforming than a kyber crystal to change the color of your lightsaber or another new poncho for Cal to wear— discoverables should go a little ways toward enhancing the actual gameplay loop if you ask me, not just the cosmetics of the gameplay loop.

Survivor? Wasn’t much better. Instead of new ponchos you would find, confusingly, new hairstyles at the bottom of supply chests. Nothing but the Rancor fight offered any kind of memorable challenge. Mini-bosses practically announced they were there just to bring you new weapons. And the final confrontation with Bode where you ride the weird force rollercoaster between platforms didn’t even have consistent internal logic.

I feel nuts about this stuff because people really love this Respawn series. It gets to strut around as “the best Star Wars experience in video games” which is personally confusing when Force Unleashed and Battlefront II and Rogue Squadron all happened.

Red Dead Redemption 2 — if you’re not fucking with it, you can always leave.

You may have memory-holed it, but Fox had to come out with a statement after the initial screenings of The Revenant in 2015 putting in no uncertain terms that Leonardo DiCaprio’s Hugh Glass had not been violated by a bear. It’s a gruesome scene in any case, because you’d expect a mauling to be brutal, short, and ugly, implied by frantic cuts and screams, the carnage left at least a little bit to the imagination. Instead it was brutal, protracted, and ugly— almost as if the bear had malice of forethought, found pleasure in it. And you just spend so much time watching it happen that you may come up with stories to distance yourself from what you’re seeing. About why it happened, about how it definitely wouldn’t have gone down like that if you were there.

But a bear is, you know, a bear. A 600-plus-pound killing machine with 4-inch claws on every paw, each of which has the surface size of a manhole cover. And you would be a fur trapper with a bolt-action rifle. Think about that. When you and Josiah light out for O’Creagh’s Run in search of the Legendary Grizzly pelt in RDR2, success seems inevitable.

I’m here to tell you that it's a totally different situation when you’re charged down for the first time. And what’s worse is that you’re given a number of chances— as your player dies, and it looks like it hurts the whole time they are dying— to button-mash your way out of being mauled to death. When you lose your rifle and you’re knocked to the ground, your player pulls out a buck knife. When that inevitably doesn’t work he may try for his sidearm. And finally when that doesn’t work, the screen goes dripping red and you spawn half the map away, half the day having passed since you were eaten alive. I felt a keen sense of injustice and raced back for a rematch. But the game only spawns its Legendary animals once a daylight cycle— meaning a lot of guesswork about the distance from the event area that effectively resets it, and the location of the prize, which can shift a bit, depending.

So I waited. And searched. And waited. And searched. For days (in-game days, real-life hours). Eventually I just got on with the story missions, resolving to come back later in the game when I was kitted out and nearly invincible. Because what else was there to do?

Sekiro — you can always change your mind, that’s how you know you’re not dead.

I wrote something about this game at my last job for something called the ‘Social Distancing Diaries’ during the pandemic— the series was equal parts “what I wore today” and “please like my sport,” but I couldn’t say much of it was of use to the reader either as a recommendation, or as critique. I was complaining about how hard Sekiro was while attempting to appreciate Activision and FromSoftware’s execution on a straightforward action-RPG. I felt a way about having it published, since I hadn’t even made it to the first mainline progression boss before filing. I didn’t touch the game again until last summer, when I decided it was the best action-RPG I’ve ever played.

There are precious few opportunities for something to grow on you when you’re working as a critic, mainly because there’s often no news to peg a rehabilitated opinion to. Revisiting things happens on a 5-, 10-, 20-year cycle, and it’s mainly selling a consumer’s prior experiences back to them at a 2000-word ad-supported premium. I may yet write about how Sekiro “does” the Sengoku period or pen a “love letter” to the game’s “action cancel” mechanic, which lets you check swing your sword if following through an attack would leave you vulnerable to a counter. (Those Jedi games don’t have it!) But I’m ashamed to have ever been part of the “games are just too hard now” commentariat.

In actuality, the game is so fair that I can’t believe I ever complained about it. This isn’t to say Sekiro is not difficult. But the combat does make a lot more sense when you remember that Activision got their start making rhythm games, because that is all Sekiro actually is. Nailing down spacing and gauging the cadence of your opponents attacks to exploit them, which you can do without special moves, gadgets, or gimmicks. You only need to deflect, attack, leap, or dodge in the correct order. I hardly even played for the plot— after a while, staging through the game begins to feel a little bit like rejigging a rubix cube. It was about the time that I started making those kinds of observations, and trying to beat the gauntlets of strength with the sound off while listening to podcasts, that my grade school friends staged an intervention. This was after I’d already beaten the game four times in a row.

I still think it’s pretty funny that this is the only game I’ve platinumed, and that I’ve logged more hours in it than FIFA.

Returnal — hell is what you make it.

There’s a sequence in Christopher Priest’s Black Panther run where Martin Freeman, T’Challah’s terminally mawkish White House attache, is held captive by Mephisto, the Marvel version of the devil. In Mephisto’s realm, which is basically hell, Freeman is surprised to find not fire and brimstone and flayed bodies, but a public school blacktop with a jungle gym, a swing set, and an angry mob of his grade school bullies. Worse, he’s in his underwear. It’s a quaint way of illustrating self-destructive tendencies, but poignant all the same.

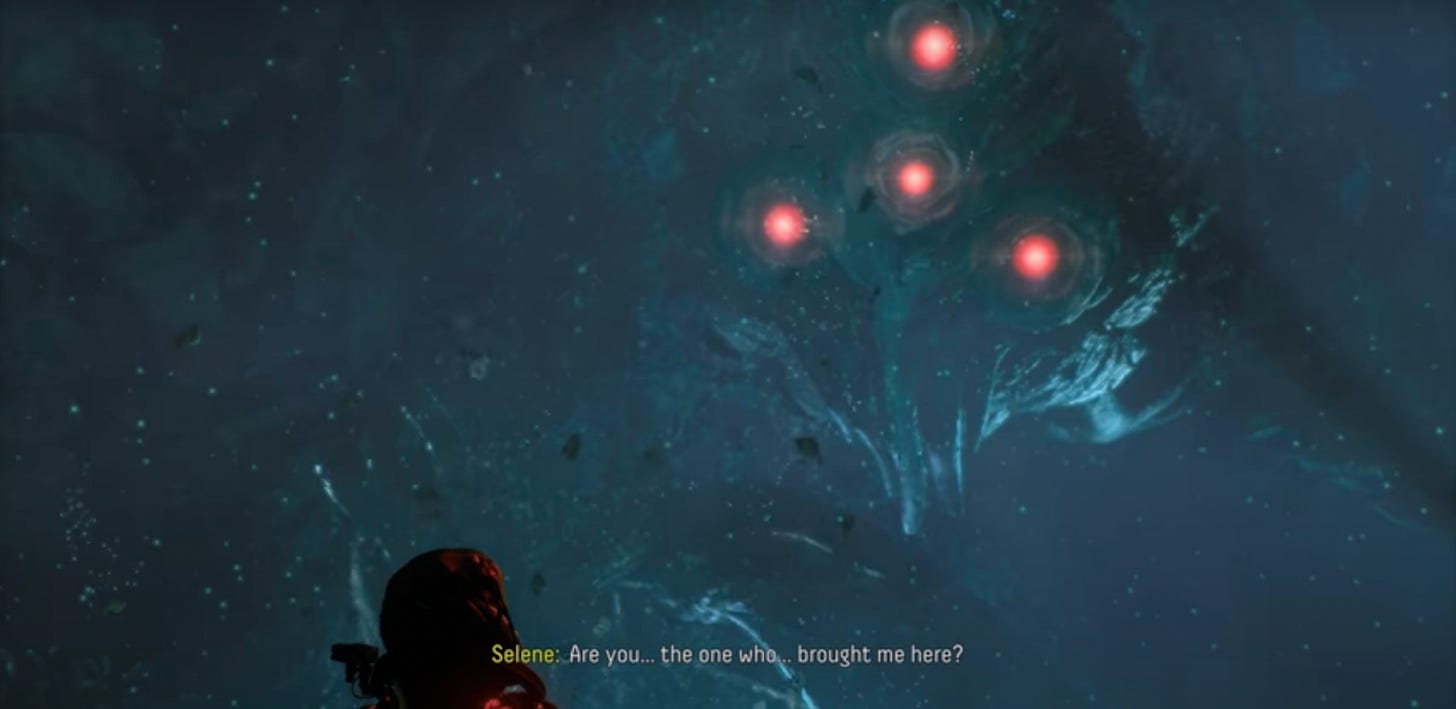

On the surface Returnal is a bullet-hell, roguelite, alien-survival sim where you are sprinting through the biomes of a strange, changeable alien planet that exists outside space, time, and apparently reason. As Selene lives the same day over and over, killing indecipherable beasts and uncovering her own corpse more than once, Returnal hints at what pulled her into the planet's orbit, why she can’t leave. There are sins in her past she needs absolution for, and as you spend more and more time running and shooting and dying and discovering, the planet becomes an outward manifestation of her guilt. Selene’s mind subsequently unravels and she learns too little about herself too late, and though the boss battles are enthralling, and felling them brings a sense of achievement, I can’t say that beating this game feels like winning. At the end, Selene doesn’t find anything like redemption; it hardly seems she even wants it.

Like Selene, we’re doomed to repeat the same mistakes unless we forgive ourselves for who we’ve been, not because we deserve it, but because we have to.